|

|||||||||||||||

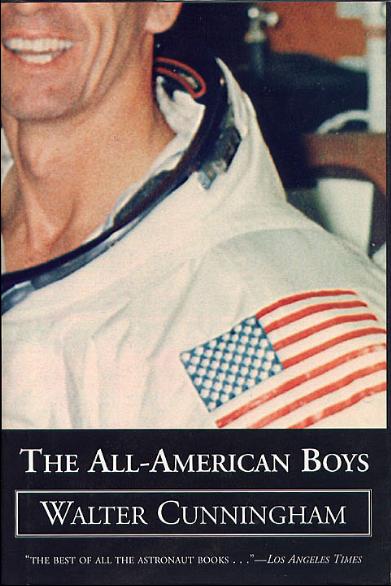

“The All-American Boys” Apollo 7 astronaut Walt Cunningham takes an unvarnished look at America’s space program by Michelle Evans, June 2004

“In The All-American Boys, I really try to personalize the space experience,” said astronaut Walter Cunningham, “and answer the question of what kind of people do these things.”

The persona of the American astronaut, especially during the early days of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo, was that they were all molded from the same cookie cutter: upright citizens, extolling the virtues of mom and apple pie. At least, that was the way NASA wanted us to see them.

Today, things are much different. We have tell-all books on famous people coming out all the time. If you were not around during the 1960s, you may not even realize how well the wool had been pulled over our eyes. In the case of astronauts, the primary example of the book that opened our collective eyes to the reality of the truly individual astronaut is Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff [1979].

Two years before Wolfe published his book, Apollo 7 astronaut Walt Cunningham was the first to write the book that broke the astronaut cookie-cutter mold. Reading his book shows the many similarities to what Wolf later wrote. This gives added authenticity to the more famous work, and provides a stature well deserved for Cunningham.

Walt’s book was written just a few years after he left the space program. It is now over 25 years later. With this in mind, Cunningham headed back to the keyboard and has now given us a complete update of his famous work that takes us back to the early days of spaceflight all the way through the disaster and aftermath of the Columbia accident.

This update provided OCSS another exciting opportunity for our members to meet and hear what an astronaut in his position had to say. On October 18, OCSS presented a fine space artifact display in support of the lecture and book signing event held at the Reuben H. Fleet Science Center in Balboa Park, San Diego. Exactly 35 years earlier, Cunningham was mid-way through the 11-day mission of the first Apollo spacecraft, Apollo 7, with crewmembers Wally Schirra and Donn Eisle. Their trailblazing effort, on the heels of the fateful Apollo 1 fire, paved the way for later flights to land on the Moon.

“Usually people just refer to me as an ‘ancient astronaut.’” he told us as he began his talk. “My wife reminds me that I am more and more like an old television set: the instant on is off, the color’s fading, it’s taking longer to warm up, and the vertical hold isn’t what it used to be.”

Much of his lecture did not deal with his Apollo mission, but on the space program as a whole. He told us, “today, the public pretty much takes space for granted most of the time. I really can’t blame them. That’s kind of the American character. But every once in a while, something comes along like the Columbia disaster, and all of a sudden the public is grabbed right by the heart.”

Walt’s most heart-felt concerns deal with international cooperation in space, especially with the Russians. International programs are what we all think are the way to go. We have talked about that fact many times in this newsletter. However, in Walt’s opinion, when looking from an engineering, as well as financial standpoint, maybe it isn’t the best way to proceed.

“What I have against the whole situation [of Russian participation] is not carrying their weight in a partnership. We had seven astronauts go aboard the Mir space station. They lied about conditions on board. I write that up in the book as the most dangerous time ever for American astronauts. I honestly believe that.

“At the time that that commitment was made in 1993, President Clinton was told that it would look like he had some sort of foreign policy initiative, it could improve relations between the countries. So, he dictated that we would invite them into the International Space Station program, the first phase of which was that we would send astronauts to Mir.

“So here we are. The Russians are on the ropes, practically bankrupt. We’ve transferred probably three to five billion dollars into the Russian space industry. We’ve kept them alive, literally. They’re now a full partner on the International Space Station, and that’s costing us a fortune that you’ll never see showing up on any budget. From the day that we agreed to bring the Russians in as partners, we had to commit immediately to change from a 34 degree inclination orbit to a 51.5 degree orbit. That’s because that’s the only place that they can reach with their Soyuz and Progress launch vehicles. [Now] every shuttle orbiter that has to go to the space station has to fly with 30 percent less payload in order to get up there. Over the life of ISS, that’s 35 to 40 extra missions that are going to have to be flown, at a cost of some $15 to $20 billion.

“My complaint is that we’re not telling the truth about what the partnership is costing us and that the Russians don’t carry their weight.”

“All that’s now said and done, and now look what happens. We have the Columbia disaster and, if we didn’t have the Russians, I don’t know what we would be doing. So let’s hope that sometime in the future this pays off in some other way because this really has been a case of the Russians ripping us off one more time.”

Walt talked further about the Columbia accident, its aftermath, and our future direction in space exploration.

“I think that the shuttle orbiter is the best vehicle ever built to take humans into space. I’ll go out on a limb and also say it’s the safest. I can’t imagine how many failures we’d have had if we’d tried to fly a hundred Apollos, but it would have been a lot. They’ve had two failures out of 113 missions. In each of those cases it wasn’t the shuttle orbiter, it was another part of the system like the solid rocket boosters or external tank. It all came about because of the same complacency and self-confidence, and not having the kind of attitude we had during the 1960s and early 70s. With Columbia, though, I can’t blame the people who made the decisions during the mission, because that was the natural thing you’d expect given that they had gotten used to flying the launch vehicle through the insulation storm. Here we had the shuttle orbiter, the most magnificent flying machine ever developed, and from the very beginning, it was intended that it would never contact anything. They wouldn’t even let it fly through rain drops, yet they were perfectly willing to let it fly through a barrage of insulation.”

As for the future, Walt had this to say, “First and foremost, we need to get the shuttle back in the air as soon as possible, and we need to complete the ISS. This probably won’t happen. We’ve spent 90 percent of the money to get 10 percent of the capability. They really need to spend the last 10 percent of the money and get what I think will be more than 100 percent of the capability. The shuttle orbiter is capable of flying again today and most of the astronauts feel the same way.”

But what about a new direction for NASA? Walt said, “NASA keeps asking what can we do to rekindle the enthusiasm. Well, if you look back on it, it was pretty doggone simple. We had a mission that had never been done before. Everybody was excited. It was impossible to go to the Moon, but we did it. It was a Buck Rogers kind of event, out there doing the impossible. In short, NASA has got to do something imaginative, like go to Mars or return to the Moon. It has to do something to capture the public’s imagination. I think Tom Wolfe said in his book, ‘No bucks, no Buck Rogers.’ I want to turn that around today and say ‘No Buck Rogers, you’re not going to get any bucks.’ Let’s get on to Mars, because it’s the only thing I can think of that has the potential to justify the kind of dedication, courage, and the risks to which the astronauts are going to be exposed.”

On his Apollo 7 mission in October 1968, there were many tensions with the ground, primarily because of arguments that Wally Schirra had with Mission Control. The entire crew became tainted because of that, and none of them ever flew in space again. However, even with that negative impression, Walt wants to assure us that he still has the utmost respect for the people with whom he worked and flew.

“The best memories I have are of flying with Wally and Donn. These were people we didn’t have a warm affection for, but we had strong respect for each other. We would bet our lives on the other guy, and we did. You come away from that with that sense of camaraderie, this sense of respect for people that you knew would give their life for you.”

Many of us can relate to Walt’s life growing up and being labeled as a “nerd.” His message to the youth in the audience that day is appropriate and should be shared with anyone who thinks that science is cool, yet still feel they must fit into the “in” crowd.

“My brother was a little embarrassed because they called me a nerd, because I was reading a book all the time in the five minutes between classes. But, it’s like I tell them: ‘The nerds inherit the Earth!’ So don’t give in to peer pressure, because most of those peers of yours are not going to make it. Most of those guys and girls out there are going to fail by your standards. So have enough self confidence to go your own way.” XXXX |

|

|||