|

|||||||||||||||

An Insider’s View of the Space Race Gemini and Apollo astronaut Thomas P. Stafford describes his experiences by Michelle Evans, August 2003

Seeing the Earth from the Moon is a rare privilege. In fact, only 24 people have ever witnessed this magnificent event firsthand. As Tom Stafford, commander of Apollo 10, put it: “You know you’re a long way from home when you see that sight.” Unfortunately, only 18 of those astronauts are still alive, since it has been over 30 years since the last time anyone has seen it for themselves. “I hope that number stays at 18 for a long time,” quips Stafford.

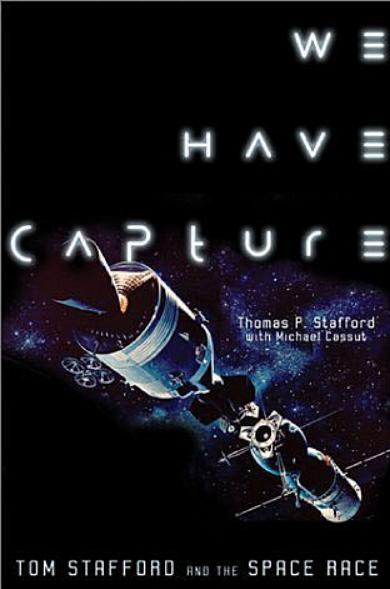

The occasion for these words was a book tour attended by Stafford and his co-author Michael Cassutt on March 23 at the Reuben H. Fleet Science Center in Balboa Park, San Diego. Like many of his colleagues, Stafford has chosen to publish his autobiography. These memoirs are invaluable insights into a time that is fast receding from us, the first age of space exploration. This was a time when anything seemed possible and landings on the Moon were just a stepping stone for further reaches into the cosmos by humankind.

“It was a wonderful time to be on the program,” Stafford said, “because President Kennedy had made the goal that we would go to the Moon and safely return, within the decade.” He added, “Now, I like that term ‘safely return.’

“At the time, we were obviously in a tremendous race,” he continued. “A race against time because of the time limit President Kennedy had set for us. Also, we were in a race against the Soviet Union. It was a difficult race because they were very successful at keeping the details of their program secret, whereas ours was open to the public. Where [the Soviets] were going, their end goal, we did not know. But we knew we were in for a heck of a race. It was a great time to be there because every mission that we would fly would be something new, that had never been done before.”

Lt. Gen. Thomas Patten Stafford, Jr. (USAF-Retired) entered the space program in September 1962 with the second group of Americans to be selected for that honor. Often called “The Next Nine,” Stafford’s group included Neil Armstrong, Frank Borman, Pete Conrad, Jim McDivitt, Jim Lovell, Elliott See, Ed White, and John Young. Quite a distinguished group of people to be associated with.

His first flight aboard Gemini 6 in December 1965 paired him with Mercury astronaut Wally Schirra. The primary purpose of their flight was to be the first to rendezvous and dock with another vehicle in orbit, a crucial step to accomplishing a manned landing on the Moon. An Atlas rocket launched their Agena target vehicle, but it exploded, leaving them with nowhere to go. A brilliant plan was hatched to launch a second manned Gemini which would serve as the new target vehicle. Gemini 7 was launched without a hitch, but the first attempt for Gemini 6 didn’t go quite as well.

As Stafford explained: “We got down to three seconds, two seconds, the engines started to shake, rattle, and roll. Then suddenly, at T-0, the engines shut down. That was when I was quoted as saying ‘Aw, shucks!’ and a few other words. So we climbed down out of the spacecraft, very disappointed. [It was] determined that we’d had two double failures that morning. Normally you’re not supposed to have a double failure when you fly in space. We got hit by two of them simultaneously. We had the liftoff signals and everything, but we knew in the seat of our pants that we hadn’t lifted off. I was supposed to back up Wally in pulling the ejection D-rings. We didn’t do that, which was a good thing. They found the problems and we launched three days later and we [finally] completed the first rendezvous in space.”

Just six months later, Stafford boarded Gemini 9, this time with crew mate Gene Cernan. A similar mission was in store for them when the unmanned Atlas-Agena exploded after liftoff from Pad 14. Once again, they had no vehicle to dock with. “After losing two Agenas, an Air Force Major wrote a poem for me,” Stafford told us in San Diego. It went: “I think that I shall never see, an Agena out in front of me!”

Two weeks later, another liftoff occurred with a backup docking target. Yet again, the fates conspired against them. When Gemini 9 reached orbit and closed on the Augmented Target Docking Adapter (ATDA), they found that the launch shroud was stuck in place over the docking port. Stafford dubbed it the “angry alligator” because of the half-deployed shroud. Once again, no docking, only rendezvous.

They were still left with a major mission objective, a spacewalk by Cernan. He was to work his way back to the rear of the Gemini, don an Astronaut Maneuvering Unit, disengage from the spacecraft, and take a tethered ride with this backpack. Cernan became overheated and then things really started to go wrong.

“[Cernan] said his whole back was burning up and he couldn’t figure it out. It turns out that the seven layers of insulation on his spacewalk suit had torn right through on his back and the flux of the Sun was coming right in. (When we landed a couple days later he still had a second degree burn on his back.) Then the moment the Sun went down, zap, he completely fogged over. He absolutely could not see.

“Then when he tried to hook up to the rocket pack to use that communications system, we lost one-way of the two-way system. Now he could hear me and I could hear some static from him, so we got a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ binary system worked out. I told him, [that] when we got into sunrise and [if he] didn’t defog, we’re calling this quits. So at ten minutes after sunrise, he still couldn’t see, so I told him to go ahead and come back in.

“He got hold of some hand holds and started working his way toward the hatch. Finally, I could see him and I reached over and grabbed one of his feet and turned him toward the Sun in hopes that he would defog. Still didn’t work, so Gene pushed down real hard with his nose and rubbed a little hole in the fog. That gave him his first visibility. I pulled and tugged to get him inside, then we dogged the hatch and repressurized. When he took off his helmet, it looked like he’d been in a sauna about an hour too long. His face was absolutely pink. Gene lost ten-and-a-half pounds in two hours and ten minutes outside. That is not a good way to lose weight!”

Stafford and Cernan would serve together again on Apollo 10. This was to be the dress rehearsal in May 1969 for the lunar landing attempt on Apollo 11 two months later. Everything went fine as the lunar module Snoopy dove to within less than ten miles of the surface. The spacecraft was not equipped to land, but that didn’t stop an exuberant Cernan from shouting to Mission Control in Houston, “We is low. We is down among ‘em Charlie!”

Then things went wrong. “The whole lunar module started tumbling end-over-end at about 60 degrees per second,” said Stafford. “That’s when we forgot we were on hot mic. Apollo 10 became X-rated at that time!”

If they didn’t stop the tumbling fast, they could black out and crash into the Moon. “I just reached over and blew off the descent stage since there’s a better torque-to-inertia ratio, since all the thrusters are on the ascent stage. We try to simulate everything , but we’d never simulated that sort of an emergency.”

Apollo 10 returned safely, paving the way for Neil, Buzz, and Mike. Stafford had one last flight into space. This time it was aboard the very last mission ever flown by an Apollo spacecraft. In the spirit of cooperation with their Cold War rivals, President Nixon had signed an agreement with the Soviet Union to fly the first ever international spaceflight, the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. In July 1975, Apollo 18 docked with Soyuz 19, and when the hatches were opened between the two spacecraft, a handshake was shared between Tom Stafford and his Russian counterpart, Aleksei Leonov. This set the stage for the later Shuttle-Mir program and eventually the International Space Station project.

As Stafford recalls: “Of the four times I flew into space, [Apollo-Soyuz] was the most difficult for me. And it wasn’t the technical part at all. It was the language training. I would speak Russian to them and they would speak English to me. With my Oklahoma accent, learning the Russian language was really a bear. Alexi was a real card. At one of the final press conferences before we launched, a reporter asked Aleksei how we were going to communicate. He said, ‘Oh, we speak three languages. We speak English, we speak Russian, and we speak Oklahoman.’”

Today, Stafford is still involved with space. He served as a consultant with the Columbia Accident Investigation Board and had this to say: “I think we’re all convinced that number one, we’ll find out what happened, number two, we’ll fix it, and number three, we’ll go fly again. And that’s what we’re going to do.” He is also proud of the avenues he helped to pave with our former rivals, “I think it’s important that we have the Russians as our partners on the International Space Station, because the Russians are going to have to carry the water for a while. The space station will go on and I’m very glad that I’m involved.” XXXX |

|

|||