|

|||||||||||||||

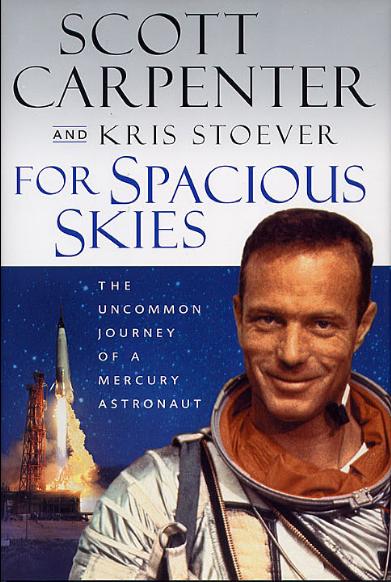

“For Spacious Skies” Scott Carpenter tells about “The Uncommon Journey of a Mercury Astronaut” by Michelle Evans, May 2003

“I’m on a very bizarre mission, and I’ve come here to tell you about it,” said Mercury astronaut Scott Carpenter when he arrived at Book Soup in Costa Mesa. “This is called a book tour and it comes to all authors I am told.”

Scott is currently crisscrossing the country, giving talks and signing autographs for his new book “For Spacious Skies.” He now joins the ranks of other former astronauts such as John Glenn, Gordon Cooper, and Gene Cernan, who have entered the publishing field. In fact, except for Gus Grissom, who died in the Apollo 1 fire, Carpenter is now the last of the original seven astronauts to provide us with his personal account of the early space program. At 78, you can see that the tour schedule is taking a toll on him but that he still loves his subject.

On May 24, 1962, Scott Carpenter became the fourth American in space and only the second, following John Glenn in Friendship 7, to actually orbit the Earth. His Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) mission launched from Pad 14 at Cape Canaveral at 07:45 am Eastern time into an overcast sky for what was supposed to be a repeat of Glenn’s flight just three months earlier. Instead, Carpenter, in his Aurora 7 spacecraft, ignited a controversy that has followed him for over 40 years.

During his flight, several problems cropped up. Soon after reaching orbit, he ejected a small balloon that was to test an astronaut’s perception of distance in a vacuum. The balloon failed to inflate and the experiment was scrubbed. Scott’s spacesuit temperature controls malfunctioned, causing him to overheat. Then his reaction control thruster fuel became dangerously depleted due to extra on-orbit maneuvering. Finally, during alignment for reentry the spacecraft’s pitch horizon scanner provided an incorrect orientation, forcing Aurora 7 to overshoot splashdown by 250 miles. For 36 minutes after reentry, it was not even known if he had survived, and it took 90 minutes until the destroyer, the U.S.S. John R. Pierce, provided pickup, since the primary recovery ship, the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Intrepid, was too far away.

A recent book by former Mercury Flight Director Chris Kraft, accused Carpenter of gross negligence during his flight and blamed him for all the things that had gone wrong. Kraft called him inattentive and unprofessional, and he made it very clear that Carpenter was never allowed to fly in space again.

Scott felt the time was right to tell his side of the story. He has now done so with the writing help of his daughter Kris Stoever. While at Book Soup, he told us, “We tell the story of my flight with malice toward no one. We set the record straight regarding that flight, and I hope that this 40 year fracas that has come my direction can finally be settled. For 40 years I have not stooped to that picayune, unimportant, and disloyal diatribe that did a lot of people a lot of damage. I hope it can be over now.”

With the gracious assistance of Book Soup manager Lawrence (pronounced “Loraunz”) Jair, OCSS was invited to set up our display case for a ten day run to help publicize the event and bring in people for the book signing on January 23. Members arrived from as far away as Lompoc and Arroyo Grande. Information OCSS provided on the Internet through CollectSpace.com brought in pre-orders from Wyoming and Alabama. On the night of the event the store was packed with approximately 200 people, who quickly bought all the available books, then sat for Carpenter’s 30 minute talk and Q&A session.

In addition to some of our regular display pieces depicting the early years of space travel, we called upon members and friends to loan OCSS artifacts specific to Scott Carpenter’s flight and the one-man Mercury space program. Most notable in this assemblage were a G.I. Joe Mercury capsule, several books and flight reports, and even a replica of the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Intrepid that was supposed to have picked up Carpenter at the end of his 4 hour 56 minute flight, all from the collection of James Busby.

From our own historian, Al Esquivel (who was late to his 7th grade junior high class to watch the launch of Aurora 7 in 1962), we placed original scrapbook pages of newspaper clippings, a Life magazine of Carpenter’s flight, and a record album by Bill Dana, who portrayed the unofficial 8th Mercury astronaut, Jose Jimenez.

On the night of the event, Chris Gillman of Global Effects provided a replica Mercury spacesuit helmet and glove that were used in the filming of HBO’s “From the Earth to the Moon.”

Racing through rush hour traffic and arriving within just a few minutes of the appointed start time of 6:00 pm, Scott greeted his audience and then told us stories of his life.

He explained why he answered the call to become one of America’s first astronauts: “I went because the orders were sent by the CNO [Chief of Naval Operations], and to a junior Naval officer, the CNO was about two steps above God! When he sends you orders saying go to Washington, you go to Washington.”

Other facets of his life were shared with the crowd. Scott told us about the special fraternity developed by the original astronauts; about their unequaled espirit de corps; about how the space race with the Russians provided a competition that “drove both cosmonauts and astronauts to better work and some marvelous experiences.”

When he decided to leave NASA, Carpenter consulted with famed oceanographer Jacques Yves Cousteau and started a second career under water as part of the U.S. Navy’s SeaLab program. One of the most interesting projects at that time was a shark chaser.

“The fact that there were sharks threatening Cousteau’s and SeaLab’s divers was unsettling to all of us. A number of our unmanned Mercury capsules had been recovered with evidence of shark attack. In one of the heat shields, a shark tooth was embedded. NASA didn’t like the idea of losing a returning space hero to a shark attack., so they commissioned the development of an electronic shark chaser. The shark chaser would emanate electromagnetic and sonic waves into the water, and chase all the sharks away. Great idea.”

After evaluation of the device, Carpenter was sent a copy of the letter with the official test results. “I paraphrase the letter, but in essence it said, ‘Gentlemen, we have evaluated your electronic shark chaser and we find it mildly repellent to sharks in both the on and off positions.’”

Scott also told us how “the real hero of this story is my mother. It makes me proud to tell you that because there are mothers here today who will one day be honored by their kids.”

I asked Scott if he would give us his impressions about the way he thought our space program is progressing today and where he would like to see it go.

He replied, “We’re headed in the right direction. We’re just not moving fast enough. We’re supporting the shuttle and the space station. Those are important things to do, but we have something much more exciting and much more important to do, in my opinion, and that is this century’s primary space goal, and that is Mars. We should be trying to get there with more vigor. We need to have more citizen involvement and support, and we probably need another [Wernher] von Braun and another [President John F.] Kennedy.”

Scott went on to offer advice for students: “For the youngsters who want to [fly to Mars] then the secret is to stay in school as long as they can, work as hard as they can, and do it in any scientific discipline that pleases them because spaceflight has answers for everyone.”

Returning to Aurora 7: Following Carpenter’s flight nearly five months later was Walter M. Schirra in Sigma 7. The accepted story goes that Wally was so incensed by how poorly Scott had performed during his flight, that Wally made sure his went like precision clockwork to absolutely prove beyond any doubt the viability of man in space.

If Schirra truly felt Carpenter had behaved in an unprofessional manner and felt antagonism toward him, then you could easily assume that they would not even be on speaking terms. However, nothing is further from the truth. They see each other often.

“I was just visiting Wally Schirra the other day in San Diego and I saw something there I thought you might be interested in hearing about. His wife has some cocktail napkins that say ‘If we can send a man to the Moon, why can’t we send them all!’ Wally doesn’t like me to tell that story.” Hardly the type of thing you’d expect if what Chris Kraft alleged was the whole truth of the matter.

The manned Mercury program lasted less than 22 months, yet its legacy will last as long as human beings fly into space. Six American astronauts laid the groundwork for everything that has transpired since. People like Scott Carpenter did what countless others had only dreamed of doing previously. Although his flight was marked with controversy, we must ask ourselves if we could have done any better. Sitting safely on Earth is no place to be a judge of someone who put his life on the line as Carpenter did.

“The story of the book is that it deals with some uncommonly fine people. We also tell the story of some marvelous unsung heroes.” For most of us, Scott Carpenter himself could be classed in this latter category. Maybe after reading his book, that will finally come to pass. XXXX |

|

|||