|

||||||||||||||

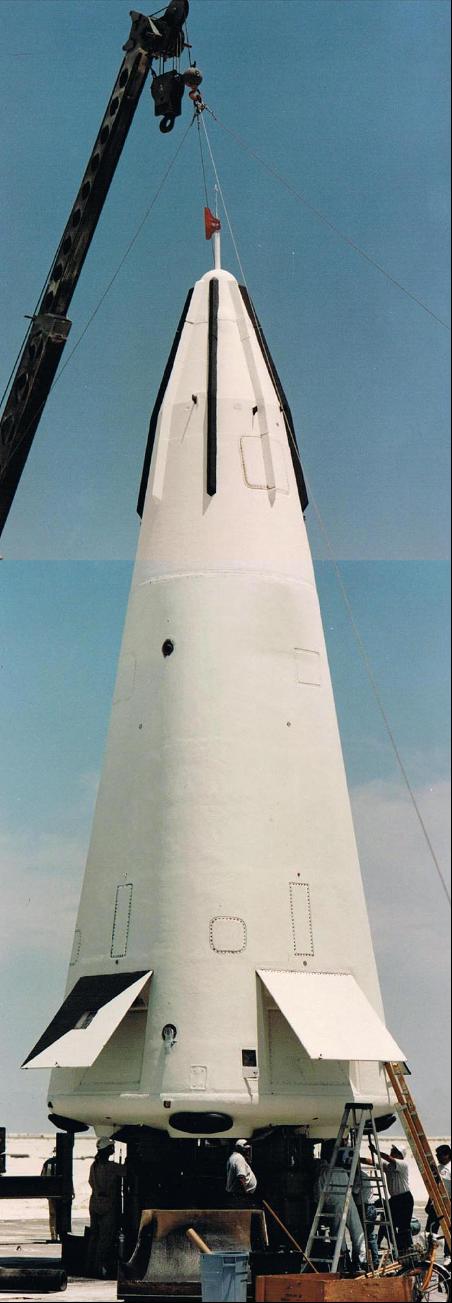

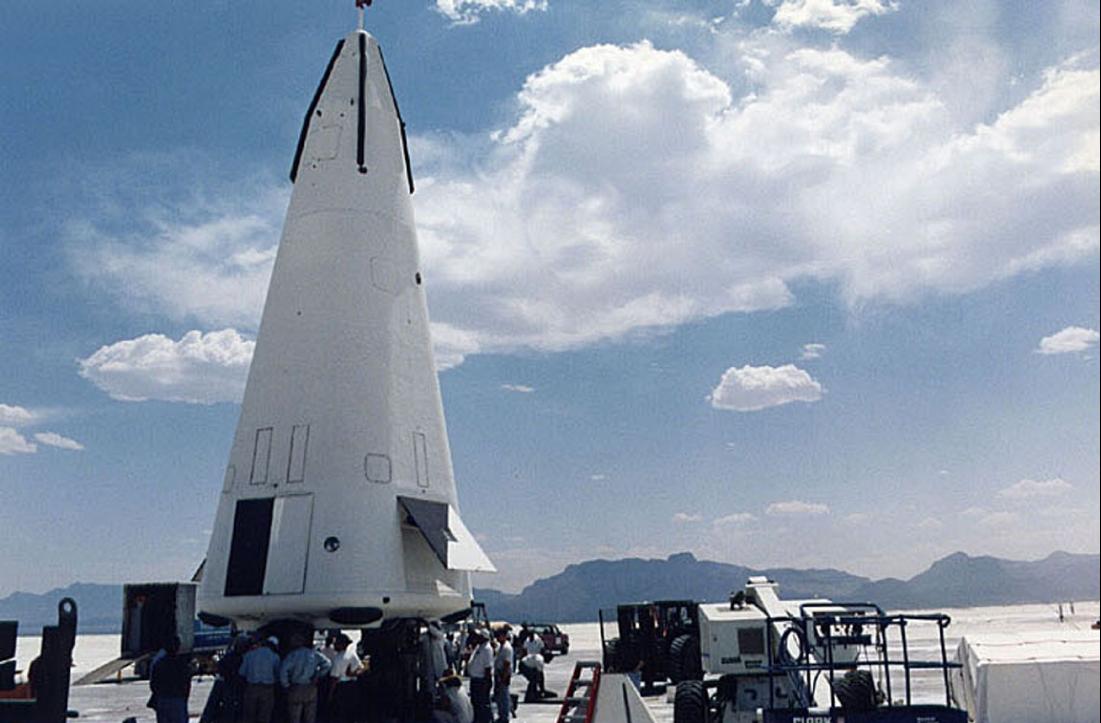

The Delta Clipper Experimental (DC-X), was returned to White Sand Missile Range in New Mexico in the Spring of 1995 for a resumption of flight testing following the hydrogen explosion on Flight 5 in June 1994.

Flights 6 through 8 would consitute Phase 3 testing on the DC-X, at which point the rocket would again return to the McDonnell Douglas facility in Huntington Beach, California. At that time, NASA, at the direction of Administrator Dan Goldin, would take a leading role in continuing the program. The vehicle was upgraded and returned to flight status for a final 4 missions in 1996. |

||||||

— DC-X Flight 6: 16 May 1995 — |

||

I returned to White Sands to see the next flight in the DC-X program, after the vehicle was rebuilt following the problems that occurred on Flight 5. |

||

|

|

|||

The rugged, but beautiful, Sacramento peaks on the west side of White Sands. |

The viewing stands for the press and other invited guests for DC-X Flight 6. |

|||

|

|

|||

Apollo astronaut Pete Conrad was one of the principles behind the DC-X program. Here Pete is monitoring vehicle status from the control trailer prior to flight. In both images, Pete is the one with the white ball cap on (sitting at left and standing at right). |

||

|

|

|||

Ignition and launch of Delta Clipper Experimental Flight 6 on 16 May 1995 at 09:40 MDT. Flight duration was 124 seconds. |

||

|

|

|||

At peak altitude of 4,400 feet. Inset shows a close up of the vehicle at apogee. |

Descent to landing at the end of Flight 6, with inset to show a vehicle close-up. |

|||

|

|

|||

Sitting on the landing pad after completion of the flight. |

Coming up to check out the rocket. |

|||

|

||||||

|

|

|||||

Various views showing different quadrants of the DC-X after landing. Note the black residue from the control thrusters in the image at the right. |

||

|

|

|||

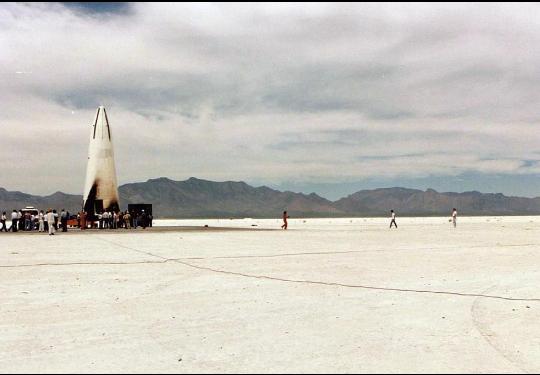

The DC-X in the distance, with the launch stand in the foreground. |

Getting a video looking up one of the rocket engine nozzles. |

|||

|

|

|||

Pete Conrad, with several other DC-X crew members, poses for a group portrait after the mission. |

Looking up into one of the four nozzles of the RL10A-5 rocket engines. Each rocket supplies 14,545 pounds of thrust for a total of 58,180 pounds of thrust at liftoff. The engines weigh 315 pounds each. |

|||

|

|

|||

The DC-X loaded onto the transport trailer. |

On the transport trailer with the hangar in the background. |

|||

|

|

|||||

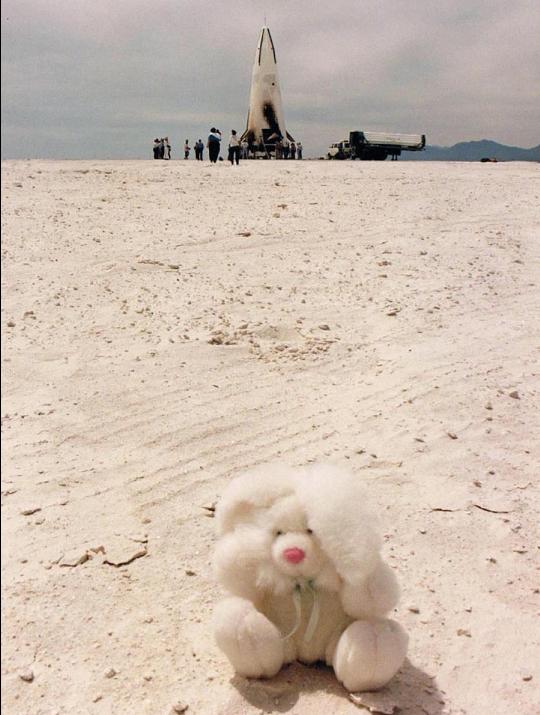

A new member of our family, Clipper, sitts on the gypsum to get his portrait taken, with the Delta Clipper Experimental in the background after the completion of Flight 6. |

||||||

Pete Conrad explains some point to the gathered media at the base of the DC-X. |

||||||

— DC-XA Rollout and Flight 10: 3 June 1996 — |

||

Following the final Phase 3 Flight 8 on 7 July 1995, the DC-X was again trucked home to California, where a new set of upgrades were installed. Most notable was an aluminum-lithium oxygen tank and graphite-epoxy composite hydrogen tank It also sported yet another new paint job, to include the designation of DC-XA (for Advanced). NASA now spearheaded the program in order to test out a slate of new technologies.

When the Delta Clipper program was first initiated, it was almost considered a rougue operation at McDonnell Douglas. Once they proved the viability of what they were trying to accomplish, all of a sudden, NASA wanted a piece of the pie as well. |

||

|

|

|||

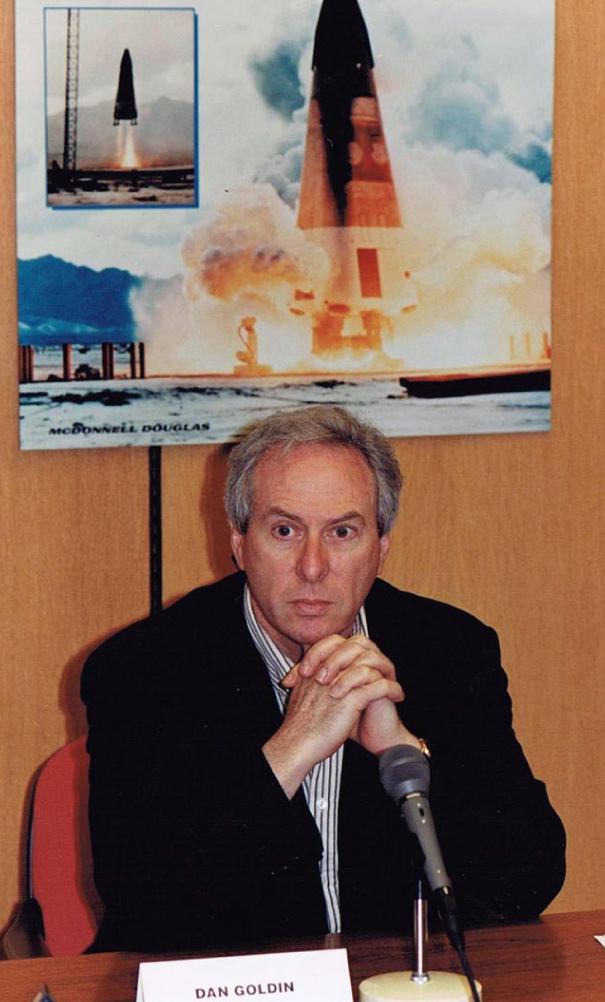

NASA Administrator Dan Goldin at the press conference announcing NASA's support for the continuation of the DC-X program, and the new designation of DC-XA. |

A newly reconstructed DC-XA rolls out of the hangar in Huntington Beach, California. This was the biggest upgrade of the vehicle since the first flight on 8 August 1993. |

||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

Gathered around the DC-XA to check out the rocket prior to Flight 10 on 7 June 1996. This flight was originally supposed to reflect the rapid turn-around afforded by a simple launch system. The second flight was to be scheduled within just 8 hours of the first launch. Unfortunately bad weather delayed the second launch, and by the time a go ahead was given, the Army personnel refused to stay around to support the launch. Flight 11 did not happen until the following day, when the personnel returned to work. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

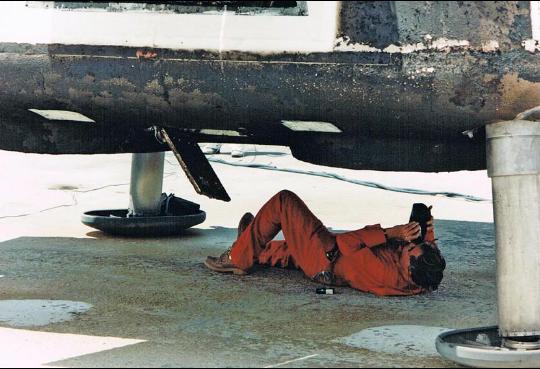

An unusual angle, checking out the base of the DC-XA. Note the heat shield tiles in between the RL10A-5 rocket engines, and the launch pad support structure. I'm lying inside one of the flame deflectors in order to get this shot. |

|||||||

The author at the MacDac facility for the DC-XA rollout on 15 March 1996. |

|||||||

|

|

|||

Close up of one of the launch pad supports, with the DC-XA launch door open. |

A technician inside one of the four body flaps to check out internal systems. |

|||

|

||||

|

||||

Technicians swarm around the base of the DC-XA. |

Close-up of one of the four landing pads in the stowed position prior to launch. |

|||

|

|

|||||

Looking up the side of the DC-XA with the Sun behind the rocket. |

||||||

A composite image of the full Delta Clipper Experimental Advanced Vehicle sitting on its launch pad, as technicians make final preparations for the misson to proceed. The difference in color balance between the top and bottom of the image came from the combining of two separate 35mm photographs. |

||||||

|

||

The Delta Clipper Experimental Advanced (DC-XA) sits on the launch stand ready for flight. The area used for the launches was near the Northrop Strip runway where the Space Shuttle Columbia landed following STS-3 on 30 March 1982. The area is also known as the White Sand Space Harbor. |

||

|

|

|||

The author stands in front of the DC-XA prior to the launch of Flight 10. |

The author with NASA Administrator Dan Goldin. |

|||

|

|

|||

Dan Goldin renamed the DC-XA as the "Clipper Graham," in honor of Lt. General Daniel O. Graham, who was one of the original instigators of the idea that became the Delta Clipper, along with sci-fi writer Jerry Pournelle and Max Hunter. |

||||

Note how much larger the crowds were for this test flight of the DC-XA versus the previous two flights documented on these web pages. |

||||

|

|

|||

Ignition and liftoff of Flight 10 at 10:15 MDT. The DC-XA ascended to an altitude of 2,000 feet. Flight duration was 64 seconds. |

||

|

||||

|

||||

Arriving for the post-landing inspection of the DC-XA. |

The scorched launch stand after the mission, with the hangar in the background. |

|||

|

|

|||

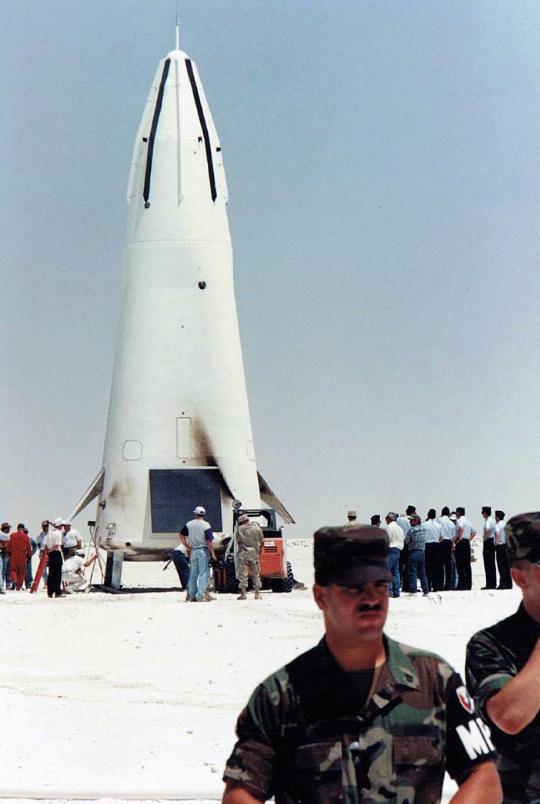

White Sands Military Police keep the press at bay while the Air Force-types (in the background on the right) inspected the vehicle. |

||||

Taking Dan Goldin's place at the podium. |

||||

After this flight, the DC-XA would only fly two more times before being lost in a landing accident at the completion of Flight 12 on 31 July 1996.

The loss was due to one of the four gear struts not extending, so that the vehicle tipped over on landing, and exploded because of the residual fuel in the tanks.

It has never been explained why the abort sequence was not initiated before touchdown since the strut was seen to not deploy. If the thrust had been brought up to re-launch to a higher altitude, the fuel could have been burned off, then the emergency parachute deployed, possibly saving the vehicle to fly another day. As it was, a great test vehicle was destroyed before its time, |

||