|

|||||||||||||||

The Astronaut As Filmmaker The final crew to repair Hubble talk of their experience by Michelle Evans, September 2009

For several years now, the sole purpose of the Space Shuttle system has been to truck supplies and components to and from the International Space Station. Following the loss of Columbia in 2003, it was decided that the only safe place to send a shuttle orbiter was to the ISS, so if something went wrong during launch, the crew would have the station as a safe haven to await pickup and return to Earth by a later shuttle. At the time, there was little that the orbiter did besides ISS runs anyway, so it was not projected to have a big impact on the rest of the program. One mission that did stand out from this was the fourth, and most likely final, Hubble Servicing Mission (SM4).

The NASA Administrator on duty at the time, Sean O’Keefe, decided that it would not be safe to return to Hubble, even though scientists had pegged this orbiting observatory as the most important scientific instrument in current use. The Hubble Space Telescope was designed from the beginning with service calls from visiting astronauts in mind, so O’Keefe’s decision caused great controversy. Almost immediately a way was sought to get astronauts safely back to Hubble.

Under a new NASA administrator, Michael Griffin, the SM4 mission started to take shape. First up was the idea of having a second Space Shuttle ready at the launch pad on standby so if anything went wrong, the rescue mission could be launched from the second pad quickly enough to get to the stranded crew before their supplies, and more importantly, their air, ran out. Mission STS-400 was thus born and the Endeavour made ready to assist the STS-125 Atlantis crew that would be on orbit.

Numerous delays marked the launch of this mission. The most significant was the addition of a new piece of hardware that needed to be changed out. The Science Instrument Command and Data Handling (SIC&DH) Unit on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) had failed just a month prior to the originally-scheduled October 2008 launch. Pulling the flight spare that had been in storage for nearly 20 years and getting it checked out and cleared for space pushed the mission into late Spring 2009. Two scientific instruments, the Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) and the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3), were slated to be added to Hubble, as well as repairing the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS). In the end, the SM4 flight would be the most arduous repair mission ever to be attempted by astronauts in space.

You’d think that with all the work to be done on orbit, the crew would have little time for anything else, yet one major objective of the mission also became to properly document their work with over 30 different cameras, still and video, along with a giant 700-pound monster loaded in the payload bay to record the first-ever 3D IMAX film of the Hubble Space Telescope. Even loaded with a film magazine that was several feet in diameter, and a mile’s worth of film, just eight minutes of footage could be captured.

Three-time Space Shuttle astronaut Scott D. Altman commanded the mission, with rookie pilot Gregory C. Johnson in the right seat. Atlantis lifted off on mission STS-125 from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39A at 2:01 pm, Monday, May 11, 2009, on the shuttle system’s 126th mission. Also aboard were five fellow astronauts who would grab and repair the HST: Mission Specialists John M. Grunsfeld, Michael J. Massimino, K. Megan McArthur, Andrew J. Feustel and Michael T. Good.

Over the following 13 days, the crew did an exceptional job of repairing and returning to orbital service the giant space telescope. Throughout the flight they continued to document their work so those of us on Earth would be able to vicariously experience some of what they accomplished.

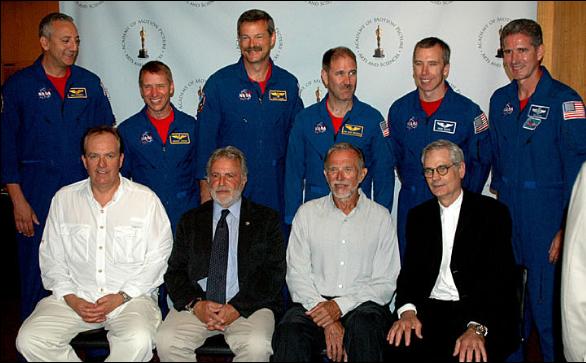

Less than two months after Atlantis reentered and landed in the high desert of California at Edwards Air Force Base, the crew (sans McArthur, who was busy supporting the next Space Shuttle mission to ISS) all gathered on July 14, at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Hollywood to share their experiences in space with the general public for the first time, The giant Samuel Goldwyn Theater was packed with hundreds of people, including several members of the Orange County Space Society who were able to attend.

Hosting the presentation were Caleb Deshanel and John Dykstra. Deshanel served as the Director of Photography in the 1983 seminal film, The Right Stuff, and has a long career in motion picture photography and directing, including being nominated five times for an Academy Award. Dykstra cut his teeth in special effects working for the legendary Douglas Trumbull (2001: A Space Odyssey) on films such as Andromeda Strain and Silent Running, before branching out in 1977 to design the special effects in the original Star Wars. For that work he garnered his first of two Academy Awards.

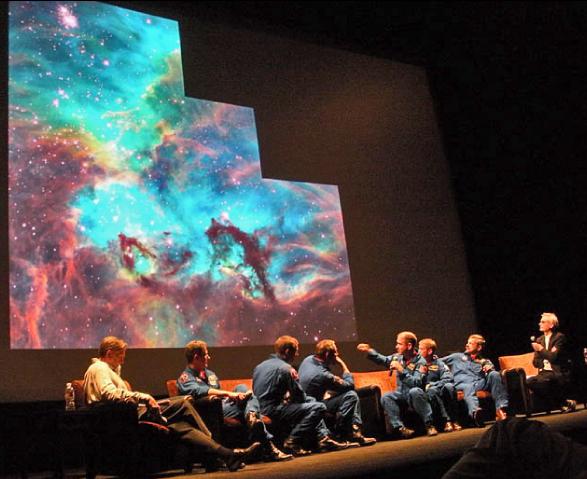

Deshanel and Dykstra brought the STS-125 crew onto the stage at the front of the theater, where they sat to discuss their mission, and specifically the recording of all they did with the various still and video cameras, including the IMAX 3D film camera loaded into the Atlantis cargo bay. Altman and his crewmates answered questions and talked a bit about one aspect of the flight while photographs were shown the giant screen behind them.

Then a break occurred where video from the mission was shown. In this way, they worked through the entire mission from launch to landing. Of course the part that most captivated the audience were their descriptions of the EVAs (or spacewalks) which comprised the bulk of the repair mission to Hubble.

The one member of the crew who could not participate at the Academy event was Megan McArthur. On board Atlantis, Megan was the crew member who had actually grappled Hubble from orbit on the third mission day, locking it delicately into place on a turntable device where the four EVA astronauts could do their work over five successive days. Those five spacewalks all went amazingly well when you consider that the Atlantis and Hubble were speeding together through space at 17,500 miles an hour, orbiting at over 300 nautical miles above the Earth‘s surface. With no air friction, it is similar to just floating in a giant tank of water—without gravity tugging constantly at you. In fact, it is in a large pool at Johnson Space Center, Houston, where the astronauts practiced their choreography in space, long before leaving the launch pad. These hundreds of hours of simulation made the whole thing seem almost routine once they were actually on orbit.

Nothing ever goes completely as planned, however, as the crew told a rapt audience in Hollywood. Bolts would not come undone or parts might not fit the way they were supposed to. These sorts of things create havoc with mission planning. Case in point was during the mission’s fourth EVA when a stripped bolt on a handrail blocked their access to a critical component that had to be repaired. Michael Massimino (nicknamed “Mass”) was outside with Michael Good (nicknamed “Bueno”), tugging at the handrail, to no avail. Finally, Mass received permission from Mission Control to literally just rip the handrail away from Hubble, if he thought he could manhandle it safely. With Bueno’s help and guidance, Mass did the deed. It is probably the first time in space history that anyone purposely broke something!

By the time the final servicing mission of STS-125/SM4 was completed, the Hubble Space Telescope had been the recipient of 23 EVAs, amounting to approximately 160 hours of work outside in the vacuum of space to repair and upgrade the huge scientific instrument. HST has revolutionized astronomy since it was launched in April 1990, and had its first servicing mission in December 1993 to correct the flawed optics that generated such bad publicity for the space agency. Nowadays, hardly anyone even seems to remember those harsh days when Hubble was considered a joke about government incompetence. Instead, the photos and data returned flood scientific institutions, classrooms, and public science centers around the world, inspiring awe and wonder at what can be accomplished with imagination and good engineering.

With the amazing work performed by this crew, Hubble is expected to live at least another five years, although it may be much more. HST is in the best condition, with the most capable instruments, it has ever had since inception. The new scientific discoveries that will come out of this mission are awaiting those who are eager to get a look at the cosmos through Hubble’s new eyes. And yet without the astronauts who were willing to put their lives on the line over and over again throughout the years, Hubble would have died an early death. Altman, Johnson, Grunsfeld, Massimino, McArthur, Feustel and Good showed us all how invaluable people are in space exploration and operations. This lesson should never be forgotten as we forge ahead.

Out of all they accomplished during that historic spaceflight, they were able to come back to Earth and share their experiences and vision with the Academy audience. And part of that will be shown to a much wider audience in 2010 when the IMAX Corporation will release a 3D film about the Hubble Space Telescope, with highlights filmed on the giant format camera by these astronauts. All of the IMAX space films have received great critical acclaim and wide popular audience acceptance. With the love affair most of us already have with Hubble and its unique vision of our universe, we should be in a for a heck of a ride next year. XXXX |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||