|

|||||||||||||||

Earthrise: The Spirit of Apollo In December 1968 the crew of Apollo 8 left the Earth for the Moon by Michelle Evans

With so much turmoil in the world today, and the shock and surprise by people who seem to think something like this could never happen, they need only look a short 40 years into the past to see this is not the first time, and certainly not the worst time.

In December 1968, what is often considered one of the worst years in American history was finally, and mercifully, drawing to a close. It had started at the end of January with the Tet Offensive in Vietnam. A quagmire within a quagmire, with fighting in the streets of major cities, and a message to the United States military that we were never going to win. It lasted over eight months, yet the war persisted for many years more. On April 4th, coincidentally, the same day the second test flight of the mighty Saturn V Moon rocket took place, Martin Luther King was assassinated. Just two days more than two months later, Presidential hopeful Robert Kennedy followed King into the abyss at the tip of an assassin's gun. By the end of a very hot August, the entire country was in turmoil. Student protesters to the Vietnam war took to the streets during the Democratic convention in Chicago. One of our own OCSS members was beaten by police during that struggle.

Our space program had been bogged down by recovery from the tragic events of the previous year when we had lost the crew of Apollo 1 in a horrible fire. But it was this recovery from that event which finally ended the tumultuous year on a high note, a note like no other before or since: the flight of Apollo 8 to the Moon.

On December 11, the San Diego Air & Space Museum organized a 40th anniversary reunion of the crew who made that flight, and allowed many of us to relive those moments that changed our world forever. Those participating included the Apollo 8 crew of Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders, along with many other astronauts, flight controllers, and others who had all made it happen.

Glynn Lunney was one of the Apollo flight controllers, and he told the gathered audience that “there were a number of people [in the United States Congress] that were wondering if we should cancel the program or we should continue with it. Frank [Borman] endured a lot of interrogations and spent a lot of time there talking to people. As we moved along, there came an appropriate time where the program began to have confidence, that we had a handle on what we needed to fix the spacecraft and go forward. When Frank was satisfied in his mind, he talked to the people in Congress. I’m going to paraphrase what Frank said at that time. You can look at it as a declaration of clarity that Frank provided to the program. He said, ‘Look, we have fixed the spacecraft. We know what we are doing. We know what we have to do. It is time to finish talking. It is time to tell us to go fly Apollo.’”

This growing confidence in the spacecraft, coupled with the fact that the Lunar Module (LM) that would be needed to actually land on the lunar surface was months behind schedule, opened up an intriguing possibility in the mind of NASA Deputy Administrator George Low. Instead of waiting for the LM to be completed, how about if, instead, the Apollo Command/Service Modules (CSM) were to fly a solo mission all the way to the Moon itself? This would be the ultimate test of that spacecraft to test deep-space navigation, the ability to test the service propulsion system (SPS) rocket motor under real circumstances, and so much more, not least of which would be the ability to trump the Soviet Union, which was rumored to be nearly ready to send their own manned circumlunar flight into space. Thus the flight of Apollo 8 was born, commanded by Frank Borman with his crew of Jim Lovell and Bill Anders.

All this was predicated on the first Apollo CSM test flight going exactly as planned. So, after Wally Schirra and his crew performed a perfect orbital checkout of Apollo 7 in October 1968, the way was officially cleared for the Apollo 8 crew to then take their spacecraft all the way to the Moon, slow down into orbit, spend nearly a day circling our nearest celestial neighbor, taking photographs of potential future landing sites, fire their SPS to blast out of lunar orbit, and reenter the atmosphere of Earth at lunar return velocities with nearly twice the energy as any previous Earth orbital mission.

As Lunney pointed out in San Diego last month, “The decision has been variously described as bold, dramatic, pivotal, leapfrogging, and indeed the Apollo 8 decision was all of those things in terms of what it accomplished. And it was even more than that.”

With all the preparations behind them, the Saturn V was ignited at 7:51 am EST on the chilly Florida morning of December 21, 1968. Seven-and-a-half million pounds of thrust pushed the behemoth off the pad and into the clear blue Florida sky and toward space. Bill Anders, the only rookie of the mission, found the powerful launch fairly disconcerting, feeling that the simulator had not been an accurate representation of what was happening. “During launch, on the first stage,” he said, “the Gs build up to six Gs, or something like that. Then, right at the end of the burnout, the engines suddenly cut off, the retrorockets fired, separated it, and it felt to me like I was being catapulted through the instrument panel. I threw my hand up in front of my face. No sooner got it up then the second stage cut in. Whack! [indicates his gloved hand striking his glass helmet.] I got my hand down and I looked, and here was this scratch across my helmet. I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, here it is, the rookie, and the other guys are gonna see the scratch on my helmet.’ When we got into orbit and it was time to collect the helmets, I collected them and each one of them had a scratch! We were all worried about the same thing.”

Once safely in Earth orbit, the crew checked all systems and found themselves ready for one of the most momentous occasions in spaceflight history when they were given the command by Mission Control, “Go for TLI.” This meant they were cleared for Trans-Lunar Injection, a burn of the third stage Saturn V that would, for the first time ever, send humans away from the influence of Earth’s domain and gravity, outward to another body in our solar system. Once accomplished, they would be on their way to the Moon!

Like everything on the Apollo 8 mission, this burn went perfectly, as did their SPS burn to slow them into lunar orbit. The spacecraft had been turned around for this burn so the astronauts were facing back along their flight path, unable to see ahead.

Bill Anders picks up the story from there. “Besides keeping the spacecraft running as a system engineer, I had this additional duty as photographer. NASA had come up with quite a complicated plan to photograph areas, landing sites, and other features on the lunar surface. So, I was industriously following that plan. Ironically, there was nothing in the plan about taking pictures of the Earth. There were no f-stops or shutter speeds, but of course, the sights on the Moon were pinned down to the last detail. It wasn’t until the third orbit, when Frank turned the spacecraft from going backwards to going forwards and heads-up, like a car going down the freeway, that we actually saw the first Earthrise. Everybody was just enthralled. There was a big scramble for cameras. Fortunately, Frank had agreed to take a few on board. I floated a black-and-white one over to him with a short lens, Jim grabbed one I had, and I got stuck with this long lens camera with color film. Shot about 35 shots, varying the f-stop, figuring one of them ought to hit it. And, indeed, one of them did.”

Jim Lovell, now famous for his later flight, Apollo 13, had been aboard this mission only because the original crewmember, Mike Collins, had a medical problem that necessitated Lovell to step in as his back up. As Lovell explained to the San Diego audience, “Well, sometimes in life, fate interferes with what your plans were. [When] I found out that I was on the crew of Apollo 8, I was elated. I felt that this was a chance of exploration, of adventure, of something to do that had never been done before, a chance to see the Moon as it really was, not really thinking about what the Earth was going to look like until we got there.”

As mission commander, Frank Borman had wanted only the essentials on his flight, essentials that didn’t necessarily include extraneous equipment like cameras. He had said, “We don’t need any still cameras, we’ve just got to get around the Moon to prove communications and navigation.” Jim Lovell pointed out that if this had happened, “poor Bill Anders wouldn’t have had anything to talk about. You see, Bill was a Lunar Module pilot, and we didn’t have a Lunar Module!”

Besides the famous Earthrise photo, the most memorable event of the flight was a special Christmas Eve message to the people back home on Earth. Frank Borman said, “When we were told by NASA that we would have the largest audience that ever listened to the human voice, the only instructions we got were, ‘Do something appropriate.’ That was a wonderful, wonderful comment on freedom of speech in America. I’m not sure that would happen today. It scares the heck out of me. I was very proud to be an American.”

The crew had deemed that the “something appropriate” would be to read from the book of Genesis. Although this action did later cause a minor uproar on Earth, for the most part, even those not of a religious nature were moved by the words.

As the passage reached across the cosmos and entered Mission Control, Glynn Lunney recalls, “They read the powerful rhythms and language of the verses of Genesis, and when we heard, ‘In the beginning…’ coming over the radio—a government radio, by the way—from the Moon, it kind of sent chills up everybody’s spine.”

Soon afterward, behind the Moon and out of contact, the SPS engine fired again to blast them out of the Moon’s influence and on their way home. As they rounded the Moon following the successful burn, knowing that the most crucial event of the mission was now behind them, Jim Lovell radioed home, “Please be informed, there is a Santa Claus.”

One last maneuver was left to accomplish, successful reentry into the atmosphere. Both Borman and Lovell had done this previously on Gemini 7, almost exactly three years previously. But even they were surprised by what lay ahead. “When we got to the reentry,” Borman explained, “we were kidding [Anders] about how exciting that was going to be because of our experience on Gemini. Then about half way through it we stopped kidding him because we were both scared to death! But we didn’t tell Bill. The reentry to me was the most demanding part of the flight.” He continued with self-deprecating humor, “That was the only part of the flight that required excellent pilot skills because it required to dig in [to the atmosphere] then roll over, and I must say that the piloting skill on reentry on Apollo 8 was superb. It was done by the autopilot.”

Splashing down in the ocean, in the darkness of extreme early morning, with the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown at the ready to pluck them from the sea, the mission of Apollo 8 had come to an end. Overshadowed just eight months later by the spectacular landing of Apollo 11 on the Sea of Tranquility, Apollo 8 nevertheless may be considered even more important in the firsts it accomplished. As described by the current NASA Administrator Michael Griffin, “I’ve long thought that the decision to send Apollo 8 to the Moon was one of the most crucial in NASA’s history, and it might well stand first on the list.”

Today, it seems simple to think we could leave the Earth and land on another planet, but amazingly, that is no longer true. We do not have the capability Apollo gave us four decades ago. Low Earth orbit is as far as humans can now travel. Hopefully, that may change over this next decade, but we have much work to do to re-accomplish what we already so eloquently did so long ago.

Bill Anders talked of this at the San Diego event. “To me it seems a little silly that we hear comments about we have to beat the Chinese back to the Moon, or the Indians to Mars. We’re all on a little tiny planet. [At lunar distance] it’s no bigger than your fist at arm’s length. This is a puny place we live. Why can’t we go to the next puny place, Mars or the Moon, as human beings, not as Americans?”

The photograph of the blue-and-white Earth rising above the stark gray lunar landscape is an icon for the Space Age, probably the most recognizable photo of the last century. Jim Lovell admitted that it, “is not really my favorite picture. It’s the one showing the Earth how tiny it is. It just continues to amaze me that many people still think the Earth is the center of the universe. I think that if we’re having religious wars even today, it’s too bad we can’t get together on the same wavelength and realize we’re all human beings creeping around on the same little dust mote out in the left field of space.”

At the end of the evening, a very special treat was in store. Neil Armstrong, the commander of Apollo 11 and first man to walk on the Moon, provided this summation: “What an evening. We’ve been reminded tonight that it’s nigh impossible to remember Apollo without noting Jack Kennedy’s role in initiating the project. We should remember that the young President did not just pull that decision out of the air. A great deal of engineering work provided Apollo [a] foundation some years earlier. They did a great job of it. So Frank, Jim, and Bill, thank you. We salute you.” XXXX |

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

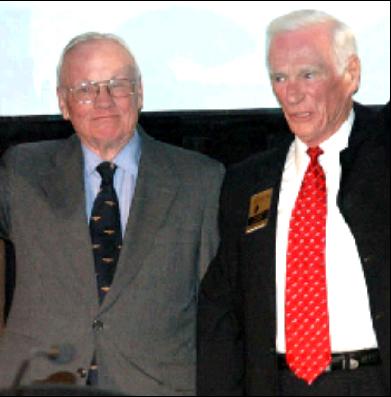

Bill Anders, Frank Borman, and Jim Lovell with a young award winner at the San Diego Air & Space Museum event on December 11, 2008. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

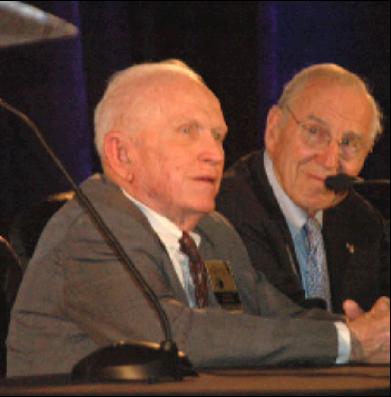

Borman and Lovell during the panel discussion. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

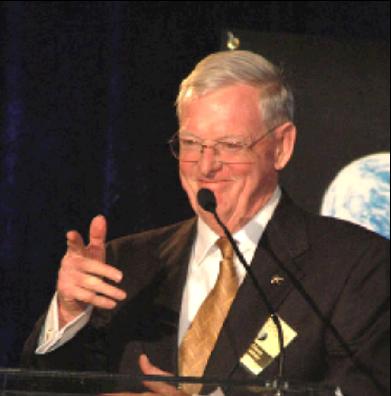

Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the Moon, with Gene Cernan, the last to do so. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

Glynn Lunney, Apollo Flight Director. |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

Launch of Apollo 8 at 7:51 EST on December 21, 1968. |

||