|

|||||||||||

|

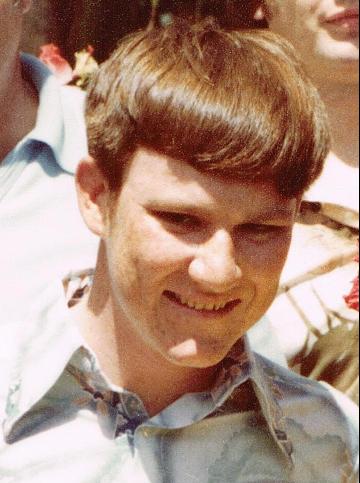

Marvin was my best friend. We served in the Air Force together during the 1970s, and he died of AIDS in 1996. This page is to honor Marvin and to talk about the AIDS Quilt panel that I designed for him. I apologize that I don't have a lot of clear photos of Marvin as, at that time, I didn't have a good camera system. The ones presented here, and on the Quilt panel were taken with a Kodak Instamatic 126 camera. To top that off, the only shot I have of Marvin wearing his Air Force uniform is an extreme blowup from a group shot on a 126 negative, so that makes it even worse!

The letter reproduced below is the one that was sent to Names Project Foundation when we presented them with the Quilt panel in January 2020. |

|||||||||||||

ATTN: New Panels 28 March 2019 The NAMES Project Foundation 117 Luckie Street NW Atlanta, GA 30303 404-688-5500

Re: Marvin Wayne Carson AIDS Quilt Panel

Hello,

This letter is to tell you about Marvin Wayne Carson. He was a typical fair-skinned, freckle-faced, red-headed guy! But what wasn’t typical was that he always seemed to be “up” about everything. I truly can’t recall a moment when Marvin didn’t have a smile on his face. He also had the distinction of being born on the day that McDonalds was founded!

He and I served together in the US Air Force during the 1970s at Fairchild AFB, outside Spokane, Washington. Marvin was the best friend I ever had, and I miss his light every day.

Marvin and I were both Missile Systems Analysts for the AGM-69A Short Range Attack Missile (SRAM). However, we worked different jobs in that specialty. He was in the Aircraft Checkout section making sure everything interfaced perfectly between the missile and the B-52 carrier aircraft, while I was in the Analysis office writing reports and histories of the SRAMs and B-52s. We lived in the same barracks, found out we had a lot in common, and became fast friends.

We went to the movies, both on and off base nearly every night, explored the area in northeast Washington, northern Idaho, and on into British Columbia. We loved to hang out at Savage House Pizza in Airway Heights. While we were having pizza there one afternoon, three girls approached us. After talking a while, they asked us out. I hesitated, figuring they had some ulterior motive for their offer, but Marvin and our other friend, Steve Noble, jumped at the chance. Reluctantly I joined the group. Turned out they were Mormons, and sure enough they were inviting us to Family Night! Over the long run, we all became good friends, even though I for one had no interest in theirs, or any other religion. Marvin ended up getting serious with one of the girls, Gale, and we began to wonder if they might get married.

In the end, that was not to be, and for a very good reason: Marvin was gay. Of course at that time, especially serving in the military long before “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” he could never be open about his sexuality. Even then, he joked about the idea of being gay, while not really admitting it as truth. I knew that Marvin was a believer, and I asked him one day in the barracks how he could possibly be gay if he actually believed in God. He laughed and said, “It’s okay. I know I’m going to Hell for that!” His humor and his smile were always infectious, but at that moment, even when he tried to make light of this idea, I felt stunned.

Part of that reason was that I had my own things to hide. I am a transgender woman, and have known since my very earliest memories, that my mind and body were at odds with each other. In the days before the internet, I had no idea what it was. The word “transgender” wasn’t even coined until I was in my 20s. I learned very early to hide who I am from everyone, even myself.

As often happens with trans people, I tried to come to terms with it by getting good at hiding. But that didn’t turn out to be the case. A couple of people in our barracks found out about me. They pounded on my door while I cowered inside. I hid for hours, until they went away, but they told everyone they came in contact with about what they knew. What saved me was that no one believed them because everyone knew they both hated me with a passion. Most people ignored it, but I knew I was no longer safe in the Air Force, and decided to end my career when my current enlistment was finished.

Very soon after this incident, on Memorial Day weekend, Marvin and I decided to meet his parents over in the Grand Coulee area for a weekend of camping and hiking. I had met them many times over the years as we used to go across to Bellingham, Washington, where they lived, to hang out in our off time. On that particular trip to Grand Coulee, we left after work at Fairchild for an evening drive west on Highway 2. There was little traffic, and as we drove through the night, our normally boisterous conversation was nonexistent. Finally, Marvin broke the silence, asking me the question I knew was on his mind: “Were the stories true?” I just stared straight ahead into the dark and choked out that it was an obvious fabrication by these guys who were out to get me. I hated myself for the lie, but I was deep in the closet. I’m sure he felt the truth, but Marvin didn’t press the issue further. I was so immersed in my little bubble, that it was many years later before it dawned on me that Marvin probably had something to share with me that night as well.

Marvin finished his six years in the Air Force a few months before I did. One of the first things I did after settling into civilian life was to contact his parents in order to reconnect with Marvin. His mom answered the phone, and when I asked the question, she got very dark, gruffly saying “I guess you don’t know?” I had no idea what she was talking about, so she went on abruptly, “He’ll tell you.” I immediately called Marvin. He laughed and said his parents had disowned him because he had come out as gay. He waited for my response, maybe thinking I would hang up on him. Instead, I said, “That’s stupid! How could they do that to you?” I made it clear that I valued him as a great friend, and didn’t care at all about his sexual orientation, but I was devastated about how he had lost his parents.

I never had a better moment to tell him about my being trans, but even then my denial was complete, and the thought never even entered my mind. Marvin had moved to Anchorage, Alaska, and was working for Arco at Prudhoe Bay. We kept in contact by phone, and I was hoping to find time to make a trek to Alaska to see him in person. Unfortunately that trip never materialized because Marvin was diagnosed with HIV, and he moved to San Francisco where he could get better treatment at the Veteran’s Administration Medical Center there. Since I was living in southern California, the trip to San Francisco was an easy one, and we were able to get together many times over the next dozen years.

Just over a year after I got out of the military, I met and fell in love with a beautiful woman named Cherie Rabideau. For some unexplained reason, I told her that I am trans on the very first day we were together. She didn’t run away, and we’ve been together ever since! She also joined me on trips to see Marvin, and loved the time we all spent together. I am so happy that she got to know him as well.

Marvin fell in love, too. His name was John, and he worked for American Express Travel. They lived together in a cool apartment with large, airy spaces, and lots of birds! But not all was perfect, as Marvin’s HIV morphed into AIDS in the mid-1990s. He went downhill quickly, and it was a terrible day when John called to tell us that Marvin had died on September 11, 1996.

What made it even worse was that his mother, Pauline, who had disowned him completely, immediately stepped in and took Marvin away from John. He was born in Henryetta, Oklahoma, and they decided to have him buried there, next to Marvin's father, William (Bill), no matter Marvin’s or John’s wishes!

Even at the end I never said a thing to Marvin about my being transgender. I think back to that night in the car in 1979, and how different things might have been if I had told him the truth. It is the single biggest regret of my life.

I always felt that at some point, I had to find where Marvin was buried, and no matter what it took, I was going to go there and finally have that talk with him that I never could in life. I found that spot in Henryetta, but I kept putting off the trip. One reason was that, now that I have finally come to terms with who I am, and was able to successfully be accepted as the woman I have always been, that this might not be the safest place for me to travel. But then Cherie mentioned the one thing I should have thought of myself a long time ago. She said “I wonder if anyone ever did an AIDS Quilt panel for Marvin?” I immediately went online to see, and no one ever did that in his memory. Obviously, this was what needed to be done, so I got to work designing the panel. It took months, but it finally came to fruition, and I am very proud to be able to remember his legacy in such a way.

Thank you for The NAMES Project and for all you have done to raise awareness of the wonderful people who have been taken from us long before their time. I am honored to be able to tell you about Marvin.

Michelle Evans

XXXX |

||||||||||||||

Marvin on 10 March 1976 at Fairchild AFB, Washington. The full group photo showing us in front of the last AGM-28 Hound Dog missile at Fairchild is seen below. Marvin is second from right. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

Marvin and I visited Grant County Airport in Moses Lake, Washington, in November 1974 to watch FAA flight test certification of the Concorde. They flew the supersonic transport into Alaskan airspace from this base to verify ice buildup and mitigation on the vehicle. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

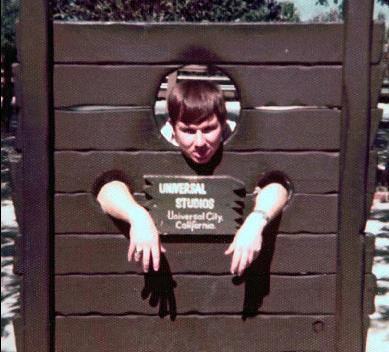

Marvin and I visited Universal Studios in Hollywood during a leave from the Air Force. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

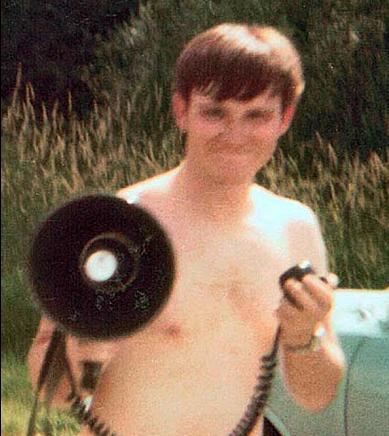

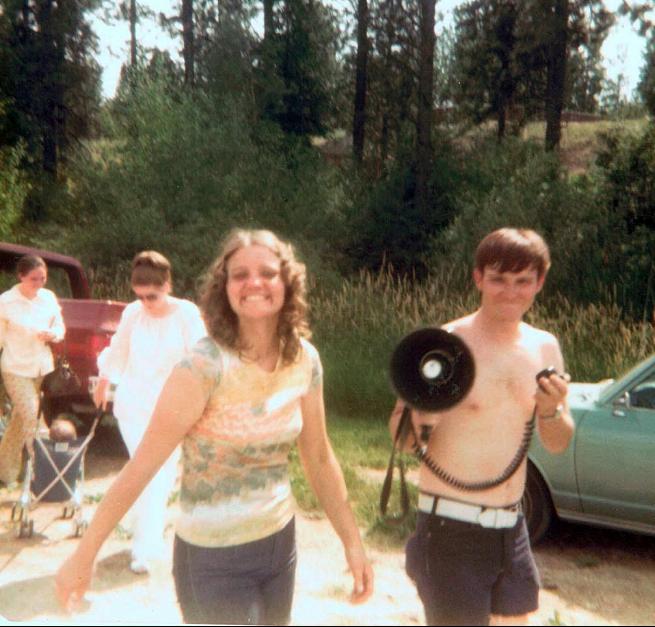

Marvin clowning around with the megaphone at the Fairchild Recreation Facility on the shore of Medical Lake, Washington. |

||||||||||||||

|

||

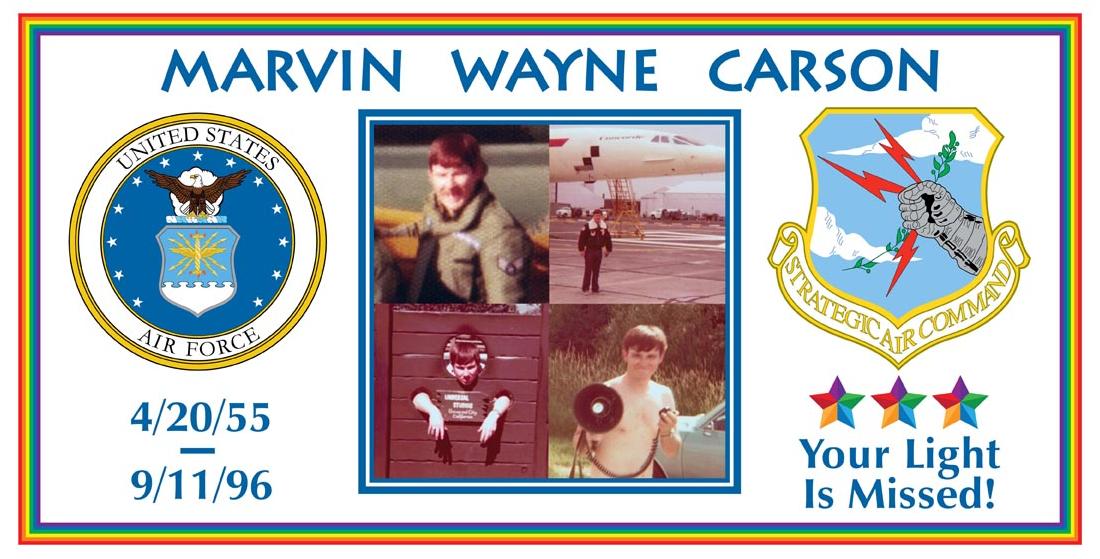

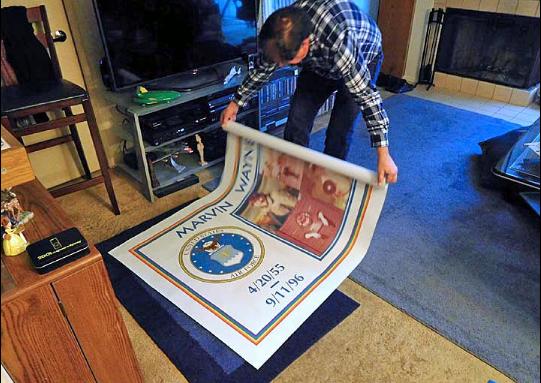

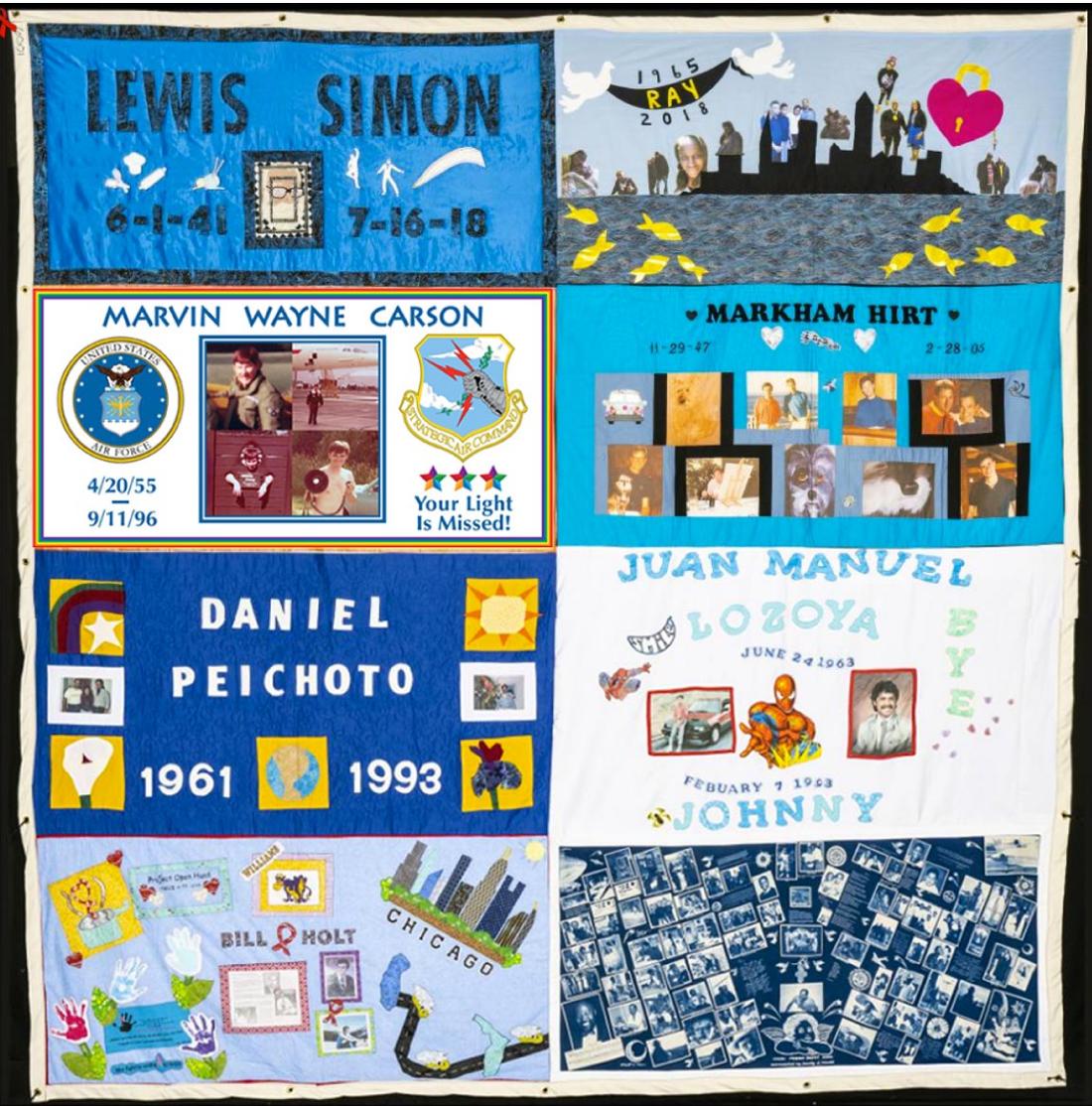

The AIDS Quilt panel honoring the life and service of Marvin Wayne Carson. The actual panel is 3x6 feet. |

||

|

|

|||

Marvin in Hawaii, 1977.

Marvin with Gale at a 92nd MMS (Munitions Maintenance Squadron) picnic at the Fairchild AFB Recreation Area near Cheney. A cropped version of this photo was used on Marvin's quilt panel, and is seen above the quilt panel image to the left of the letter. |

||||

— Creating the panel: 22 July 2018 to 17 February 2019 — |

||

|

|

|||

Bob Kline did a fantastic job of taking my design and upscaling it so that it could be dye-sub printed. He found the proper cloth banner material, as well as putting a white flood coat on the image so that it was crisp, clear, and sharp. Above shows Bob unrolling the quilt panel for the first time on our living room floor. |

||

|

||

Cherie and I with Marvin's panel soon after Bob brought it to us. |

||

— Oklahoma Trip: 21 April to 5 May 2019 — |

||

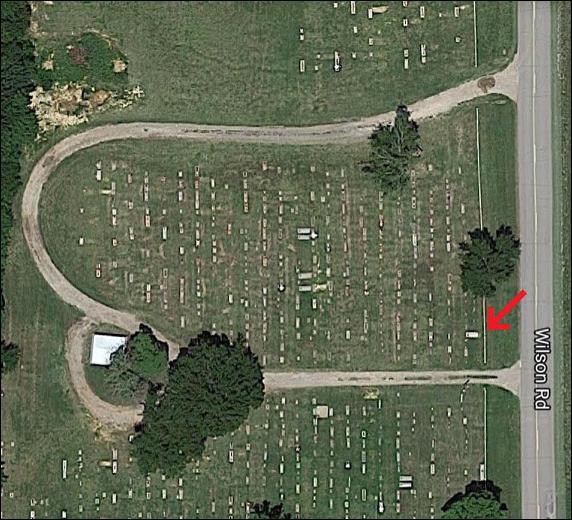

Once the panel was completed, we drove to Henryetta, Oklahoma, in order to take it to Marvin's gravesite at the Wilson-Salt Creek Cemetery. We arrived on the morning of 29 April. |

||

|

|

|||

Henryetta, Oklahoma. Literally a crossroads of America. |

||

|

|

|||

We stopped at Rheba's Flowers to pick up a bouquet for Marvin. |

Rheba's owner was very helpful in finding the perfect flowers for Marvin. |

|||

|

|

|||

Integrity Funeral Services helped us find the location of Marvin's gravesite, and was also helping with the upkeep of his internment plot at the request of Marvin's mother. |

||||

We arrived at the cemetery around 10:00 am CDT on 29 April. |

||||

|

|

||||

Satellite view of the Wilson-Salt Creek Cemetery from Google Earth. Marvin's gravesite is located by the red arrow.

Cherie and I with our new bear, Marvin (from Rheba's Flowers). The AIDS Quilt panel has been unrolled and placed atop the site. |

|||||

|

||

|

|

|||

Some of our kids were there to honor Marvin as well. |

Marvin also wanted some time alone with his namesake. |

|||

|

|

|||

Cherie places a kiss on Marvin's grave before we left. The headstone next to Marvin marks his father, William W. Carson, a World War II U.S. Army veteran, who died at age 62 in 1984. |

Marvin was born on the same day that McDonald's was founded, so before we headed out of town we stopped at the Henryetta McDonald's to hoist a fry in Marvin's memory. |

|||

|

||||

The American flag flying in the breeze above the entrance to the Wilson-Salt Creek Cemetery in honor of Marvin, and all veterans interred at the cemetery. |

||||

|

|

|||||

|

||||||

— Quilt Delivery to San Diego History Center: 14 January 2020 — |

||

The next step in the journey for Marvin's quilt panel came with our delivery of the panel to the San Diego History Center. They had an AIDS Quilt block on display that was nearing the end of its run, so it would soon be transferred back to the NAMES Project. Marvin's panel would be packaged and sent back with the block.

Joining us for the trip to San Diego was Bob Kline and Debbi Bennett, and once we arrived, we were also joined by Francis French. Our point of contact at the museum was Tina Zarpour. |

||

|

|

|||

Bob, Michelle, and Cherie unfurl Marvin's panel in front of the AIDS Quilt block on display at the San Diego History Center. |

Tina Zarpour, Debbi Bennett, Bob Kline, Michelle Evans, Cherie Rabideau, and Francis French. Marvin's panel has been re-rolled, and is on the bench in front of us. |

|||

|

||

Once the History Center had the block packaged for shipment, Marvin's quilt panel, along with all the paperwork, was added to to box to be sent to The NAMES Project in February 2020. The following month the Covid pandemic shut down operations across the country, which created a lengthy delay in Marvin's quilt panel being incorporated into the overall AIDS Quilt. Also, during this time, The NAMES Project was dissolved, and is now known as the National AIDS Memorial. The Quilt itself was re-located from Atlanta, Georgia, to San Leandro, California. |

||

— Incorporation into the AIDS Quilt: 5 September 2021 — |

||

With the lifting of pandemic restrictions beginning in the Spring of 2021, Marvin's panel again started moving through the process of being photographed, then becoming a part of the AIDS Quilt. In early September it became official that Marvin's panel was sewn into Block 6001. A more than three year journey to honor Marvin's life was finally completed. |

||

|

||

Marvin's Quilt panel is number 3 on Block 6001. Others sharing this block are Lewis Simon, Ray (last name unknown), Markham Hart, Daniel Peichoto, Juan Manual Lozoya, Bill Holt, and Ronan Berri. |

||

— National AIDS Memorial Offices: 17 September 2021 — |

||

|

|

||||||

The sign on the door of the National AIDS Memorial offices in San Leandro. |

|||||||

Michelle and Cherie in front of Block 6001 on the morning of 17 September 2021. |

|||||||

|

|

|||

The entirety of the AIDS Quilt, each block lovingly folded and archived. |

Gert McMullin was our host, here with Cherie, with Marvin's block behind them. |

|||

|

|

|||

One small part of Gert's work area with many momentos. |

Another view of the facility. The Quilt is on the left, and the workspace is on the right. |

|||

— AIDS Memorial Grove and the Circle of Friends: 19 September 2021 — |

||

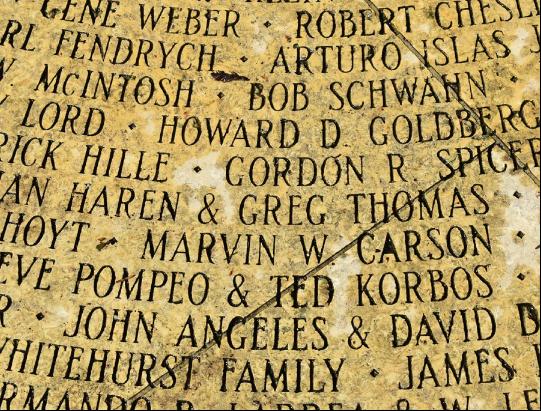

Marvin's partner, Jon Ward, left a memorial for Marvin in the AIDS Memorial Grove in Golden Gate Park. He dontaed an engraving to the Circle of Friends in honor of Marvin in December 1996. The engraving can be found in the 24th circle out from the center, almost directly in line with the marker for East.

I wasn't exactly sure of the location when we arrived that afternoon, so I started counting the rings of names outward to the 24th circle using my cane. Out of the more than 2500 names there, my cane landed directly on Marvin's name! |

||

|

|

|||

Cherie stands near Marvin's name. |

The center of the Circle. Marvin's name is at image center, third row from the bottom. |

|||

|

|

|||

Close-up of Marvin's name as honored by his partner Jon Ward. |

Cherie touches the engraving. |

|||

|

|

|||

One small part of the beautiful and peaceful AIDS Memorial Grove. |

A sunburst in the Memorial Grove for Marvin. |

|||